Phil Izzo at the WSJ:

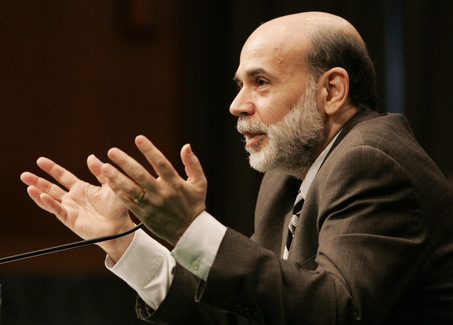

Economists are nearly unanimous that Ben Bernanke should be reappointed to another term as Federal Reserve chairman, and they said there is a 71% chance that President Barack Obama will ask him to stay on, according to a survey.

Meanwhile, the majority of the economists The Wall Street Journal surveyed during the past few days said the recession that began in December 2007 is now over. Battling the downturn defined most of Mr. Bernanke’s term, which began in early 2006 and expires in January, and economists say his handling of the crisis has earned him four more years as Fed chief.

“He deserves a lot of credit for stabilizing the financial markets,” said Joseph Carson of AllianceBernstein. “Confidence in recovery would be damaged if he was not reappointed.”

The Journal surveyed 52 economists; 47 responded.

Free Exchange at The Economist:

Other economists are being careful to play it safe, pointing out the many shoes which might yet drop and noting that the severity of the recession might make forecasting unusually difficult. Those are fair points to make; while I’d say I agree with the the positive forecasts above, I’d also suggest that the margin of error is quite high. Much has gone right in recent months, but much may yet go wrong.

Vincent Fernando at Clusterstock

But what should Bernanke’s game plan (or exit strategy) be for all of this?

Randall Kroszner at Financial Times:

Leaving a financial crisis is like leaving an awkward social gathering: a good exit is essential. In 1936-37, the Federal Reserve made a colossal mistake in its “exit strategy”. This time round it is crucial that central banks get their timing right.

[…] The big challenge is for central banks to avoid deflation and provide the monetary accommodation to restore economic growth without igniting high inflation down the line. In the US, market-based measures of inflation compensation do not suggest market participants expect inflation to move to high levels in the next decade (see chart 2). However, late last year and early this year, markets worried that deflation could grip the US economy. The proliferation of new credit facilities, expanded swaps with other central banks, and reduction of the Federal funds rate target to nearly zero for an “extended period” helped mitigate the deflation fear. The Fed’s balance sheet grew more than two-and-a-half fold during 2008 to end the year above $2,300bn as many market participants borrowed through these facilities and central banks drew on their swap lines with the Fed (chart 3).

[…] As economies stabilise and recover, central banks will face the same challenge the Fed faced in the mid-1930s: when and how to reduce monetary accommodation and prevent the large accumulation of bank reserves on its balance sheet from being lent out, causing an inflationary expansion of money and credit. A fundamental misjudgment by the Fed was to assume that, as the economy revived, banks would manage liquidity exactly as they had prior to the banking crises earlier in the decade and hold only the legally required minimum. When the Fed sharply increased reserve requirements in 1936 and 1937 (see chart 1), banks responded by calling in loans to build a liquidity cushion above legal requirements, thereby sharply contracting money, credit and economic activity.

Just last autumn, Congress gave the Fed a new tool that will play a crucial role as it exits from its unusually accommodative monetary policy: the ability to pay interest on reserves. Previously, a recovery would mean more opportunities for banks to lend and so they would draw down non-interest-bearing reserves and expand credit and hence the money supply. Interest on reserves, however, can cut that logic short by providing incentives for banks to hold reserve balances rather than lend them out, as the Federal funds rate target rises. The Fed now has a greater control over the reserve choices of banks because it can raise the return on reserves relative to banks’ lending opportunities, and thereby better manage credit and money growth in a recovery. In addition, of course, the central bank can drain reserves directly from the system through reverse purchase agreements and the sale of long-term securities from its portfolio, among other means. The ability to pay interest on reserves also allows the Fed to offer term deposits to the banks, thereby committing the depositing bank to keep its reserves with the Fed for a specified period of time.

The basic idea here is simple: if the Fed raises the rate it pays on bank reserves, banks will park money at the Fed. That reduces the amount of money they lend out. Cut the rate and banks will pull their money out and find a better use for it. Lending will increase.

Fine. That makes sense and always has, as long as you trust the Fed to handle this particular monetary knob properly. But what I still don’t get is why you’d turn this knob up during a crisis, as the Fed did last year. That reduced bank lending at a time when credit had already dropped off a cliff and was threatening to choke off the economy completely. Is there some triple bank shot (no pun intended) here that I’m not getting? Did the Fed figure that banks just flatly weren’t going to loan out funds no matter what, so they might as well pay them interest as a backdoor way of recapitalizing them? Or what? I’m still confused.

And the last piece of Fed news, Daniel Indiviglio at The Atlantic:

As widely expected, the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee decided this week to leave the federal funds rate in the 0% to 0.25% range. And don’t expect that to change anytime soon. Its press release said:

“The Committee will maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and continues to anticipate that economic conditions are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for an extended period.”The Committee also isn’t too worried about inflation. It said:

“Although economic activity is likely to remain weak for a time, the Committee continues to anticipate that policy actions to stabilize financial markets and institutions, fiscal and monetary stimulus, and market forces will contribute to a gradual resumption of sustainable economic growth in a context of price stability.

The prices of energy and other commodities have risen of late. However, substantial resource slack is likely to dampen cost pressures, and the Committee expects that inflation will remain subdued for some time.”I think that’s right, but I still worry that it might not have the political audacity to take the necessary action to keep inflation low once the economy really begins a full-fledged recovery.

UPDATE: Kevin Drum

David Rothkopf in Foreign Policy

UPDATE #2: More Drum

UPDATE #3: Bernanke is reappointed.