Richard Gamble in TAC with a provocative essay, “How Right Was Reagan?” An excerpt:

Doubting the depths of Reagan’s conservatism sounds akin to doubting FDR’s liberalism. We are so accustomed to thinking of Reagan as the pre-eminent conservative statesman of our time that any shadow on that reputation seems nonsensical. But some conservative dissidents have recently blamed Reagan for giving his benediction to the most culturally corrosive tendencies in the American character. In his recent bestseller, The Limits of Power (2008), Andrew Bacevich harshly criticizes Reagan for just this failing. Bacevich notes the irony of Carter’s seemingly more conservative plea for limits juxtaposed against Reagan’s boundless optimism. “Reagan portrayed himself as conservative,” Bacevich writes of the campaign underway in 1979. “He was, in fact, the modern prophet of profligacy, the politician who gave moral sanction to the empire of consumption. Beguiling his fellow citizens with his talk of ‘morning in America,’ the faux-conservative Reagan added to America’s civic religion two crucial beliefs: Credit has no limits, and the bills will never come due.” Bacevich charges the “faux-conservative” Reagan with nothing less than undermining America’s moral constitution, its adherence to such timeless “folk wisdom” as “save for a rainy day.”

Dissent about Reagan among conservative intellectuals goes back surprisingly far, back even to Reagan’s first term. Historian John Lukacs, writing in Outgrowing Democracy (published in 1984 and later reissued under the title A New Republic), found it necessary to put Reagan’s “conservatism” in quotation marks, calling it “lamentably shortsighted and shallow.” He conceded that much of Reagan’s rhetoric was conservative and that it spoke to certain durable conservative instincts in the American people. But overall, Reagan preached yet another version of sinless, progressive America that had more in common with Tom Paine and Woodrow Wilson than with Edmund Burke. In a chapter added in 2004, Lukacs attributed the record budget deficits of the 1980s in part to Reagan’s populist message that demanded no self-sacrifice or hard choices from the American public. They could have it all. He also credited the collapse of the Soviet Union to the Russian people’s own loss of faith in Communism and to the political skills of Mikhail Gorbachev, not to Reagan’s military build up.

In a further criticism, Lukacs traced the “militarization of the image of the presidency” to Reagan. It was Reagan, after all, who began the practice of returning the salutes of the military—a precedent followed by every president since. While doing so may seem to honor the military, it in fact erodes the public’s understanding of the presidency as a civilian office, Lukacs argued. Indeed, Fox News bears out Lukacs’s warning. The cable news giant got into the habit during the Bush II administration of referring to the president as commander in chief no matter what story they were reporting, seemingly unaware that the nation’s executive is the commander in chief of the Armed Forces of the Untied States and not commander in chief of the American people at large. If the president visits a city ravaged by a hurricane, he is emphatically not there in his role as commander in chief. If every American thinks of the president—of whatever political party—as my commander in chief and not narrowly as the Army or Navy’s commander in chief, then we have taken another decisive step from republic to empire. If every American expects the president to be the commander in chief of the economy, then we can’t be surprised by nationalized banks and corporations.

Peter Lawler at PomoCon (read the comments for the meat of the discussion):

Is the pope Catholic? Well, some think not. According to the erudite Richard Gamble, ol’ Ronald was too Puritanical in the wrong way to be conservative. He gave us irresponsible tax cuts and a “Wilson” or evangelical, transformational foreign policy. His speeches were full of an “expansive liberal temperament” that flowed from Reagan spending his wonder years in “the pietistic, revivalist world of the Disciples of Christ.” His activist faith morphed into a Christianity without Christ that became our optimistic civil religion. He had nothing but contempt for any talk about limits to our power and wealth. Real Puritans talk about original sin, personal and national guilt and all, but not the selective Puritanical civil theologian Reagan. Gamble thinks we should return, instead, to the malaisian wisdom of the 1979 Jimmy Carter, a far more authentic Christian conservative who knew that patriotism wasn’t really about getting and spending.

This article was recommended to me by the porcher page and was published in THE AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE. It goes without saying that I don’t agree with most of it, but why don’t all of you divide up into small groups and discuss. (Hint: One possible criticism is that there’s no talk about the defeat of COMMUNISM and all.)

James Poulos at PomoCon:

A semi-tangent apropos of the thread developing below on Reagan’s is-it-or-isn’t-it conservatism: it’s true that Reagan’s public brew of conservative moralism and vigilence combined with western-libertarian free-range thought, inclusive of religion, reflects in telling or cautionary ways his hodgepodge of a private life. But this has been old news since Constant, whose long tormented relationship with Germaine de Stael surely sucked more out of a man’s marrow than Reagan had lost by the time he made President. There does seem to be an inevitable — and in quarters left and right disturbing — link between the politics of independence and a culture of incoherence. The glorious jumble of conservatism, liberalism, and libertarianism on display in America since its most hashed-out Constitutional coming of age (I’ll have to leave the Civil War out of it for now) is the political byproduct and reinvestment of a culture ever without, as Philip Rieff says Tocqueville showed us, an officer class.

Mark T. Mitchell at Front Porch Republic (look at the comments there, too).

Fast-forward 29 years. Sam Tanenhaus has a new book out called The Death of Conservatism.

Lee Siegel at Daily Beast:

For Tanenhaus, the conservatives have abandoned their core values of respect for tradition and sensitivity to the necessity of change—of pragmatic, principled adaptability—for a rigid absolutism that expresses itself in a politics of destruction and mechanical negativity.The party that once stood for governmental ballast and probity in the ’50s, and for governmental order and responsibility in the late ’60s—as the liberals’ well-intentioned war and their well-intentioned welfare state came crashing down on society—now identified government itself with the forces of evil.

An interesting consequence followed. Since political power can only operate through government, the conservatives had chosen to exert their power more directly, around politics, as it were, by means of cultural confrontation, personal attack, and reflexive stonewalling. This is why conservatives seem most politically organized when out of power, and why when they attain political power, they immediately begin to act like apolitical outlaws.

[…]

What is most fascinating about Tanenhaus’s fascinating book is his nimble grasp of what Hegel called “the cunning of history.” He is ultra-sensitive to the social-psychological aspect of American politics, to the way opposing factions project themselves onto their adversary, covet and envy the opponent’s principles and social position, express antagonism by impersonating and/or parodying the enemy’s most successful values.

So, as Tanenhaus writes, the liberal rhetoric of compassion and the state’s responsibility to its most hard-pressed citizens—the poor—which led to the New Deal became the Reagan conservatives’ rhetoric of compassion and the state’s responsibility to its most hard-pressed citizens—the middle class—which led to tax cuts that undid or diminished many of the New Deal’s social programs.

Tanenhaus himself embodies this ironic complexity. He writes with warm admiration of the Ur-conservative Edmund Burke’s “distrust of all ideologies, beginning with their totalizing nostrums.” He glowingly describes how Burke “warned against “the destabilizing perils of extremist politics of any kind.” This conservative credo seems to be the root of his revulsion against today’s conservative extremists.

Jon Meacham in Newsweek:

Meacham: So how bad is it, really? Your title doesn’t quite declare conservatism dead.

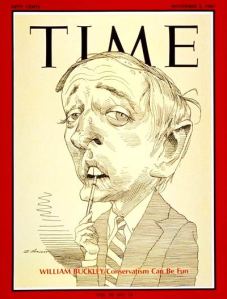

Tanenhaus: Quite bad if you prize a mature, responsible conservatism that honors America’s institutions, both governmental and societal. The first great 20th-century Republican president, Theo- dore Roosevelt, supported a strong central government that emphasized the shared values and ideals of the nation’s millions of citizens. He denounced the harm done by “the trusts”—big corporations. He made it his mission to conserve vast tracts of wilderness and forest. The last successful one, Ronald Reagan, liked to remind people (especially the press) he was a lifelong New Dealer who voted four times for Franklin D. Roosevelt. The consensus forged by Buckley in the 1960s gained strength through two decisive acts: first, Buckley denounced right-wing extremists, such as the members of the John Birch Society, and made sure when he did it to secure the support of conservative Republicans like Reagan, Barry Goldwater, and Sen. John Tower. This pulled the movement toward the center. Second: Buckley saw that the civil disturbances of the late 1960s (in particular urban riots and increasingly militant anti-Vietnam protests) posed a challenge to social harmonies preferred by genuine conservatives and genuine liberals alike. When the Democrat Daniel Patrick Moynihan called on liberals to join with conservatives in upholding “the politics of stability,” Buckley replied that he was ready to help. He placed the values of “civil society” (in Burke’s term) above those of his own movement or the GOP.[…]

Is there an analogous historical moment? Conservatives argue that this is 1965 and that a renaissance is at hand.

I disagree. Today, conservatives seem in a position closer to the one they occupied during the New Deal. The epithets so many on the right now hurl at Obama—”socialist,” “fascist”—precisely echo the accusations Herbert Hoover and “Old Right” made against FDR in 1936. And the spectacle of citizens appearing at town-hall meetings with guns recalls nothing so much as the vigilante Minutemen whom Buckley evicted from the conservative movement in the 1960s. A serious conservative like David Frum knows this, and has spoken up. It is remarkable how few others have. The moon party is being yanked ever farther onto its marginal orbit.

Daniel McCarthy in TAC:

In this interview with Jon Meacham, Tanenhaus makes like Basil Fawlty and doesn’t mention the war — the Iraq War, that is, which “serious conservatives” like David Frum supported. Tanenhaus had no problem criticizing the war until now and tying it to the Republicans’ dwindling electoral fortunes. But now that a Democrat is in office, suddenly health care is the thing that conservatives are supposedly screwing up. Even though attacks on the president’s plan have so far been rather popular.

But let’s go back to the idea that Republicans have somehow drifted away from the “conservatism” of TR. There’s a deep body of literature out there — Gabriel Kolko’s Triumph of Conservatism is perhaps the best known specimen — making the case that trust-busting actually favored big business. So perhaps Teddy and Enron’s recent man in the White House have something in common. And there’s another, more obvious sense in which movement conservatives are very much in the mold of Teddy Roosevelt — they are heirs to his machismo, nationalism, and militarism. Tanenhaus would probably agree that these are qualities which have not served the con movement well over the last four years (at least). But TR embodies them. He was the first to thump the pulpit for 100 percent Americanism, and he was much more eager to intervene in World War I than Woodrow Wilson was. TR is a great inspiration to neocons today: there’ s a reason the summer books issue of the Weekly Standard bears a cover image of Teddy in an inner tube. Yet Tanenhaus, who knows the neocons had something to do with the Iraq War and the Iraq War has something to do with conservatism’s death, praises TR and calls David Frum a “serious conservative.” The conclusion one is lead to is that Tanenhaus is so sympathetic to the social-democratic tilt of the neocons and economic interventionism of TR that he absolves them of the blame he knows they deserve for the Right’s ruin. Conservatives would be ill served to heed him. What’s needed is exactly the opposite of what Tanenhaus prescribes: the Right should sharpen its economic differences with the big-government Left while repudiating the catastrophic foreign policy promulgated by the likes of David Frum.

More McCarthy:

If all a Tanenhaus wants is a Right that is a.) a little abashed about how Iraq turned out, but not really repentant, and b.) in favor of a “pro-family” welfare state, then he already has much of what he wants, since Ramesh Ponnuru, David Frum, Ross Douthat, David Brooks, and a host of neoconservatives already affirm a program exactly like that. Hell, Karl Rove belongs in that category, too. These are the most prominent names in “conservative” print media, and fairly influential voices within the Beltway. They would all complain that the grassroots aren’t on board with their “moderate” military welfarism — the grassroots are too brusque, too bumptious, too worked up about Obama’s birth certificate and illegal immigration. But the grassroots Right is in the state it’s in thanks in no small part to the likes of Ponnuru, Frum, Douthat, and Brooks. Since their program of welfare for families doesn’t inspire anyone, their political allies wind up having to whip up enthusiasm for the military side of the program, and have to throw in some red meat about gays, immigrants, and abortion. But the NY-DC axis have no cause to complain, since that’s the only way to sell the public on their insipid welfare-warfare program. He who wills the end must will the means. The only means toward getting the Right to embrace the welfare state is to get the Right hopped up about real wars or culture wars. But that’s precisely what has cost the Right political power over the last four years.

Andy McCarthy at NRO links to James Piereson in The New Criterion. Piereson:

Tanenhaus argues that conservatives failed because—well, because they did not act like conservatives at all but rather as extremists and radicals out to destroy everything associated with modern liberalism. The paradox of the modern right, he says, is that “Its drive for power has steered it onto a path that has become profoundly and defiantly un-conservative.” According to Tanenhaus, conservatives have been divided since the 1950s between their Burkean inclinations to preserve the constitutional order and their reactionary or “revanchist” impulses to tear up and destroy every liberal compromise with modern life. “On the one side,” he writes, “are those who have upheld the Burkean ideal of replenishing civil society by adjusting to changing conditions. On the other are those committed to a revanchist counterrevolution, whether the restoration of America’s pre-New Deal ancient regime, a return to Cold War-style Manichaeanism, or the revival of pre-modern family values.” In recent years, he concludes, the “revanchists” have gotten the upper hand over the Burkeans, and have thereby run the conservative juggernaut over a cliff and into irrelevance. In an entry that gives the reader a flavor of some of the exaggerated rhetoric contained in the book, Tanenhaus writes that, “Today’s conservatives resemble the exhumed figures of Pompeii, trapped in postures of frozen flight, clenched in the rigor mortis of a defunct ideology.”These “exhumed figures” are presumably free-market economists and conservatives like Jonah Goldberg and Amity Shlaes, whose books have been critical of the New Deal, neo-conservatives who supported the war in Iraq, and social conservatives who have opposed abortion, easy divorce, and gay marriage. In Tanenhaus’s view, genuine conservatives would accept the New Deal and the welfare state as “Burkean corrections” that served to adjust the American economy to modern conditions. Nor would “real” conservatives have supported a war in Iraq that was based upon a utopian ideal of bringing democracy to the Middle East. He also thinks that conservatives should accept gay marriage as an extension of family values to a new area. The reason conservatives have not followed such advice, he says, is that their attachment to orthodox doctrine trumps the practical advantages of finding areas of accommodation with adversaries. In a most un-Burkean way, he says, they have allowed ideology to prevail over experience and common sense. Thus, as he suggests, the right is the main source of disorder and dissension in contemporary society and the instigators of the long-running culture war that has divided the country.

Employing this framework, Tanenhaus arrives at surprising judgments about some prominent conservatives—for example, that Ronald Reagan was a “real” conservative because, despite his rhetoric, he made no effort to repeal popular social programs but accepted them as an integral aspect of the American consensus. This is gracious on the author’s part, though it is a judgment that few liberals will accept simply because they are certain that the only reason President Reagan did not repeal many of those programs is because Congress would not permit it. After all, one of Reagan’s favorite sayings was that “Government is the problem, not the solution.” Reagan, like every other major Republican office-holder of recent decades, including George W. Bush and Newt Gingrich, was constrained in this area by a mix of congressional politics, interest groups, and public opinion. Tanenhaus also says that Buckley, while starting out as a “revanchist” in the 1950s, turned into a Burkean in the 1960s by his acceptance of liberal reforms, especially in civil rights.